3-D Spy Turned Chemistry Teacher (and Other Astonishing Tales from Dr. Al Trujillo)

Dr. Al Trujillo

You wouldn’t want to slam a book down in Alfonso Trujillo’s chemistry class in the early 1950s.

He was a bit anxious when he first started teaching at Carbon College. In fact, ask him today and he tells you he was downright belligerent and angry. Sleep did not come easily, and when it did, it was fitful and fraught with frightening dreams of German soldiers coming back to hunt him down.

“I tried not to think about it,” he says. “I tell you, I prayed that I could forget it and I have pretty much forgot. But in those days, they didn’t recognize this, I guess, like they do now.”

By “this,” he means post-traumatic stress syndrome. World War II ended, but it was still raging on in his mind. Back then they politely called this condition “combat exhaustion.” It was something you just didn’t talk about. Good soldiers were expected to shake it off, tough it out, keep silent about it. And so he did. No surprise then that today, 70 years since the war ended in Europe, few — least of all his students — know the un-solemnized, war-hero side of their stern chemistry and math teacher.

Trujillo’s teacher-hero distinction, however, appears to be well in hand. Jim Piacitelli took classes from Trujillo in 1962 as a sophomore and still remains in close contact with him. He says he and so many of his peers respect and revere him to this day. “People loved to be taught by him and to have their children taught by him,” he says. “For me, the experience has been after 55 years, one of deepening appreciation for the quality of individuals who taught me, especially those at Carbon College.”

Kenneth L. Gilbert was taught by Trujillo in 1965 and took the time, 48 years later, to thank him for his influence. He says he owes his 24 years as a chemist at the Idaho National Laboratory to Trujillo for helping him get his start. It only seems fitting then for Gilbert to be winding down his own career as an adjunct professor of chemistry at the Eastern Idaho Technical College in Idaho Falls.

In a letter to Trujillo on May 20, 2013, he tells his students “the reason I became a chemist was because of the inspiration and impression Dr. Alfonso Trujillo made on me. I also tell them I teach the way Dr. Alfonso Trujillo did. The fact is that if you, dear Al Trujillo, had been a physicist, I would have been a physicist. The same is true had you been a psychologist, sociologist, mathematician, etc.”

The possibility of “combat soldier” in Gilbert’s “etcetera” may be why Trujillo chose not to talk to students about his war years.

He certainly denies any hero characterization and inserts the word “stupid” in its place. And he laughs wholeheartedly as he says it. And you instantly know you are in for a ride as you settle down for a visit with this legendary teacher and former academic vice president at the College of Eastern Utah.

Trujillo speaks fondly of his years at “the college.” While he could have gone anywhere to teach, including a cushy job at a two-year college in the prospering post-war years of California, he says he chose Carbon College because the area offered him exactly what he needed back in those early years: quiet spaces and good places to hunt and fish. He also loved the classroom and took comfort in being able to explain the chemistry of carbon. It is the chemistry of war, however, with its unfathomable properties, reactions and phenomena that continues to haunt and perplex him.

It was not too many years before that he was falling out of the sky above the shores of Normandy, France, in the midst of mortar shells. He was among the throng of D-Day paratroopers floating like giant schools of medusa towards a battle that ultimately killed or wounded some 425,000 allied and German troops.

He was scared all right and during that endless plunge to Earth, he could blame no one but himself. He lobbied for the chance to be there, and not out of ignorance. He knew more about the invasion, dubbed Operation Overlord — including when it would take place — long before most. He jokes, again, that it was his stupidity that got him in that predicament. Sift through the self-deprecation and you quickly realize it was more likely his carpe diem attitude, intelligence and youthful zeal — qualities that could have led to his death but went on, instead, to serve him well through life.

Before War

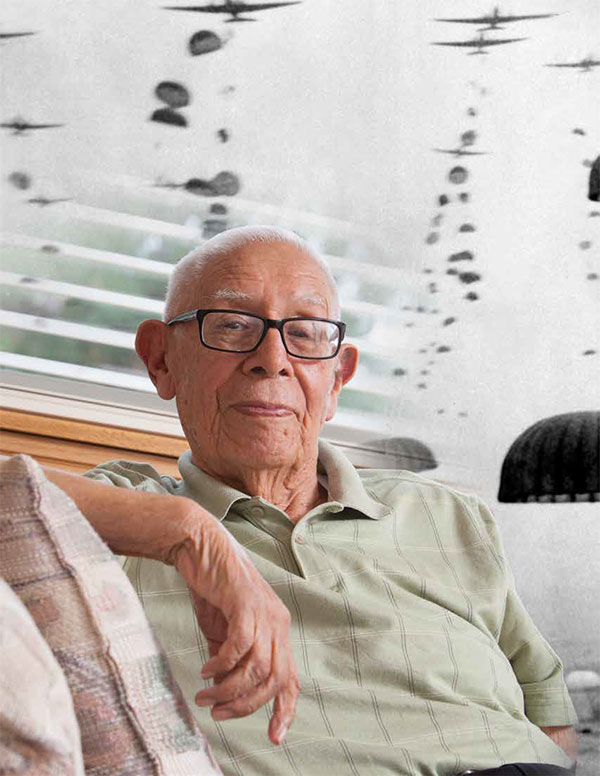

Just how a 19-year-old kid from little Manasa, Colo., got in on the early planning stages of one of the most significant battles of World War II is part of a litany of stories he strings out over two fleeting hours. His soft-spoken, but animated, voice makes you sit up close and listen carefully. His tales are sprinkled with laughter, often as chuckles ironically placed. The plush sofa of his modest ranch-style home in Helper, Utah, envelops his lean 5-foot 8-inch frame. His agile mind defies his 92 years of living as he bounces between chemistry equations and historic WW II battles throughout the interview. His full head of military-cropped hair, complements his youthful mannerisms. His olive skin remains remarkably smooth. He wears jeans and a short-sleeved shirt that fit his relaxed and comfortable demeanor. He’s had a good life, been blessed with Vera, his wife and companion of 70 years, five children, 13 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

He speaks as with surprise and delight to still be around. That sense of wonder fills his storytelling. He talks about how amazed he felt as a teenager when he learned he had taken second place in a statewide high school chemistry exam, despite not really preparing for it. It got him some early recognition and more than a few scholarship offers.

After graduating from Manasa High School as class valedictorian, he enrolled at Brigham Young University. He had other schools in mind, but his parents, devout members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, wanted him to go to BYU.

“I wasn’t too happy,” he says. “I got on the honor roll the first quarter and then second quarter I got introduced to girls (he laughs) and as a result, I didn’t do too well.”

He is placed on academic probation and called in to the dean of students. He doesn’t want to let his parents down, but his heart just isn’t in it and he decides to leave BYU. Instead, he gets involved in a federal government program that pays for training in different trades. He finds machine shops, especially milling machines, to be fascinating and takes classes. Soon after he is offered a position as a machinist at Hill Air Force Base, in Ogden, Utah. By then the U.S. war effort in Europe and the Pacific is in full bore and the base is buzzing.

Off to War

I wanted to get into the war,” he says, “Oh, boy, did I want to go. I WANTED TO GO TO WAR.”

He enlists in 1943 and is sent to Clearwater, Fla., a major training base for U.S. troops destined for Europe and the Pacific. The majority of those in his basic training are shipped to the Pacific. His wish for action is to go to Europe. He gets it, eventually, but not in typical fashion. Out of his Boot Camp group of some 100 men, he is part of a handful selected to go on to a military installation just outside of Washington, D.C.

“Boy, what did I do?” he wonders when he’s called in to headquarters. They won’t tell him. They just put him on a train bound for D.C. where he’s whisked away by a staff sergeant to “some big government building” and then given orders to report to Camp Ritchie.

He is told that not too many recruits are sent to this facility “so don’t be surprised when you get there.”

He quickly comes to know that he is at a highly classified site used for central intelligence training. He says he can’t tell anybody he is part of military intelligence, not even family members. In his second week there he begins taking military classes with majors, captains, lieutenants, sergeants and privates. He is given some tests and eventually assigned to a photo intelligence group. The U.S. military is in great need of detailed maps of Western Europe. Tourist-type maps are basically all they have at this point. Trujillo is trained to develop highly comprehensive maps from aerial photo mosaics. His task is to learn how to spot enemy tanks and rockets by using stereoscopes to create three-dimensional images. At the conclusion of his training, he jumps from private to staff sergeant.

3-D Spy

His first assignment takes him outside London, England, where, to his dismay, he does little his first month. He wants to get into the war, but all he does is tour England, including the Cliffs of Dover. He does not know at this time that the U.S. government is further vetting him. Even his parents are being scrutinized about their ancestry. The reason for this becomes clearer in time. He is to be part of a highly elite group of men and women with super security designation called Bigot – a classification above top-secret. “Why such a name?” he asks. “It was said to me that it was because we were bigoted.” He laughs.

It actually stands for British Invasion of German Occupied Territory that Churchill chooses, according to the BBC-produced History of the World, prior to the U.S. involvement in the war. Even as Eisenhower takes over the planning role, this Top-Secret classificationcontinues.

“We thought that was for the invasion that would take place,” he says. He later learns it is actually part of a ploy involving a fake army buildup under Gen. George Patton.

This ghost army of Patton’s is part of a huge deception to keep the Germans guessing at where allied troops will invade. By 1943, Germans are pinning down possible invasion sites along the coast of France adjacent to the English Channel. The port of Calais, the narrowest point between England and France, is where Patton makes it appear as if he will be leading the allied charge. So convincing is this feigned buildup on the English side of the channel prior to Normandy, that it causes Adolf Hitler, fearful of a major counter-attack at port of Calais, to insist that German garrisons guarding this region stay put, even after the massive allied invasion on Normandy.

After about a month, he and a few others are separated from the rest of the intelligence photo team.

“They told us that we had a super-top-secret classification and then I got a very thrilling experience,” he says. “While we thought the area where we were studying would be for the attack, they instead showed us a big map of the Normandy Peninsula and they said, ‘this is where the invasion will take place. As a result, you are not to discuss this with anyone.’”

If knowledge is power, then this 19-year-old boy is suddenly growing into a powerful young man. Not only does he know WHERE one of the most significant invasions in World War II will take place, he also knows WHEN it will occur, and before most everyone else.

Combine that knowledge with the photo intelligence he is helping to gather and it is not difficult to appreciate the significant role Trujillo plays in a battle that Churchill calls “the beginning of the end.”

They may not have known it then, but what Trujillo and his fellow 3-D photo spies accomplished was highly significant in the overall war effort. Trujillo, and those who preceded him in the years leading up to Normandy, painstakingly pored through photographs of French landscapes captured by cameras mounted on retrofitted Spitfires. The mosaics created from these photographs, and viewed through stereoscopes, reveal vital details such as camouflaged rockets, missiles and ships that otherwise are lost in one-dimensional images.

As a result, deadly German V1 and V2 guided rocket launch sites spread across France were being identified and destroyed through thousands of bombing missions in what was called

“Operation Crossbow” prior to D-Day. This operation virtually eliminated most all rocket threats that likely would have hampered a successful allied invasion at Normandy, according to a NOVA documentary 3D Spies of WW II that first aired July 24, 2013 on PBS.

Trujillo recalls how he first spots some sort of oblique object in his own scanning. It turns out to be a rocket with 2,000 pounds of warhead attached to it. “So there was real interest in it,” he says.

Real interest in EVERYTHING comprised of and around the beaches of Normandy. As a result, Trujillo’s team makes thorough studies of the peninsula and develop comprehensive relief maps, overlays and everything they can possibly do to provide a complete picture of what military brass and troops can expect. It even includes maps of where the beach landings and the drop sites for airborne divisions will be.

Normandy

Trujillo says the day then comes for him and other members of his intelligence group to go to every platoon commander and orientate them and staff. It was when he and two fellow officers are briefing a captain of the 82nd Airborne Division under Gen. Matthew B. Ridgeway, that they make an unusual request.

“The three of us were quite young and stupid,” he says. “We told them, ‘we don’t want to just see this, we want to get in on it.’”

That entreaty creates a bit of a stir back at headquarters. All three of these officers know too much and are, therefore, a great risk to military intelligence if they are captured. They persist though, and fly back to London to make their case. Eventually they are allowed to go, but only after destroying all their identification, including their special Bigot Neptune cards (the assault phase of Operation Overlord is code-named Operation Neptune).

They have only one more hurdle to get over, a big hurdle — none of them have any parachute training (he laughs). No glider training, nothing. They start with learning how to hit and roll on the ground and then how to collapse and fold their chutes. After that their trainers announce to them, “you’re ready to take your first jump,” he laughs. “I had never been in a (paratrooper C-47) airplane in my life (he laughs again). Once up, they drill them on the three-step procedure: stand up, hook up, check your equipment. Hooking up involves the static line. First making certain they are properly attached and second, making sure the line never gets under their elbows “or it will pull your arm right off.”

They take five jumps in all. Jump six is on D-Day, June 6, 1944, the day of the Normandy landings, the largest amphibious assault in history. It was supposed to be the day before, but poor weather conditions prompted the delay. It is during this wait that these three intelligence officers-turned-paratroopers prove especially valuable to their division. Their captain approaches them with some recent aerial photos that had been taken showing unidentified objects. Using their stereoscope training, Trujillo and his two companions determine that what they are seeing are “great big poles sticking out” that turn out to be anti-airborne obstacles with barbed wire and razor blades attached. They had not been there before, but now are exactly where the 505th would be touching ground.

“So we had to change the drop zone for the 505th,” he says. “You’ve probably seen the movie or heard about how a lot of them hit the town of St. Mere-Eglise. I was fortunate enough to apparently have a rookie pilot who got scared and didn’t give us the light to go, and so we missed our drop zone by 10 miles, fortunately, or I’d a hit St. Mere-Eglise.” St. Mere-Eglise, just six miles due west of the Utah Beach invasion site, was the first town in France under 2nd Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. Benjamin Vandervoort, to be liberated, at the cost of many lives.

After digging through the pockets of his wallet, Trujillo pulls out his torn 82nd Airborne Division Association Charter Member laminated card with the word “Secret” in the torn bottom-right corner. It is as if he thinks he needs to prove something. He even hunts down the New York Times Bestseller, D-Day, by Band of Brothers author Stephen E. Ambrose and begins reading a paragraph from it that includes his name. After all these decades, it is as though these few remaining items provide him with some tangible evidence and reassurance that this wasn’t just some crazy dream.

“So that is how I got into the airborne and my classifications… I’m not talking too much, am I?” Vera sits in an easy chair to his left, her fingers lightly tapping on her lap. You see in her slight smile that there is more to come.

On Patrol

Like the story about how he was supposed to help take and hold the line for the soldiers fighting on the beach, “but that was a mess” because of the way paratroopers are strung out across the countryside. It turns out that the wide unintentional scattering of troops becomes a tactical advantage because the Germans think they are being hit with a much bigger force. “They guessed that we had dropped whole corps of airborne in that area instead of divisions.”

Trujillo says their objective is to secure Cherbourg and the road that leads to it. “We were to take that road and hold it so that the Germans couldn’t bring their stuff up.” He’s never been back to France since the war, but he takes pride in the role that the 82nd and the 101st airborne divisions played in capturing and defending this strategically important deep-water port city. Without Cherbourg, situated at the northern end of the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy’s northwest coast of France, reinforcements and supplies from the U.S. could not have been rapidly deployed. It was strategically vital for the allies to ensure this continuous front.

He recalls how he and a fellow soldier, also a Colorado-native, stumble upon a squadron of German soldiers while on patrol — “not elite, more like home-guard, 40 or 50 of them,” he says. “When they saw us, they shouted ‘comrades!’ They surrendered!”

He says the two of them are initially astonished and don’t know what to do with their yielding enemies. After some discussion, they decide to march them back to division headquarters as their prisoners “and so we come marching in with a whole bunch (he chuckles) of Germans all ourselves, just me and him. These guys didn’t want to fight.”

And when it came right down to it, Trujillo says he didn’t want to fight either, but that was beside the point because at this stage in the war, he was in a fight for his life. He somberly recalls the first time he has to fire his gun in combat.

“I had a Thompson sub, clip of 18, and when I ran across him, I pulled the trigger. You could hear as I hit him, but I hit him in the helmet. That .45 has a kick to it, and it dropped him and by the time I realized what was happening, I kept firing. I was shooting straight up! I was so nervous, and the poor guy was trying to struggle to his feet when I …” his voice trails off.

While fighting at Normandy, his patrols typically consist of five men. In some skirmishes, they all survive, but in others, they are not so fortunate. He says his division continued to fight at Normandy for about a month before suffering a 40-percent casualty rate. “Not all dead, some were incapacitated, so they pulled us back after 30 days.”

As a ground soldier, he is classified an intelligence observer. “Not a very good title,” he quips. He heads up observation posts, sometimes ahead of the front line, sometimes on it. “There’s not really a line, it’s just a garbled mess.” His task is to observe and report back any enemy activity. In one such patrol, they establish “a dandy observation post” in a two-story farmhouse they take.

“Somehow or the other, the Germans went around it,” he says. “Well, I had one guy with me; he was kind of a jerk. I told him: ‘Don’t move out! Don’t give any sign there is life in this house! All our observations will be away from the window!’ Well, he decided to go out. When they (German soldiers) spotted him, he ran back into the house and so boy, oh boy, the mortar shells started to come in, and we scattered. I ran and jumped in this foxhole…I jumped in and saw a dead German soldier there. I didn’t know that he was dead, and so I turned my Thompson sub on him before I realized he was dead. I lost about half of my patrol at that time, but that was my job. I never got hit. I was just lucky.”

Luck with a heavenward gaze. He manages to go on and safely navigate through the maze-like hedgerows of France where Germans easily hid. “It was really, really bad,” he says. “It was scary. I remember one occasion, I wouldn’t usually pray at this time (he chuckles), but on this occasion I prayed ‘Lord, God help me…if you do, I promise that I’ll be a good Mormon and marry in the temple. I’ll do ANYTHING!” he chuckles.

He recalls a conversation he has with an atheist friend after Normandy. “When we got back to London to regroup, I saw him and I said, ‘did you pray?” and he said “of course I didn’t;’ ‘to hell you didn’t!’” Trujillo laughs.

Holland Invasion

Trujillo’s stories weave battles together as if a compilation of trailers from all the great World War II films. He is at once narrator, character and living witness. It is one thing to watch movies or read books about these events and very much another to actually hear from somebody who was there. You see, for example, not just the disappointment in his eyes,

but you hear the frustration in his voice as he describes missions and operations that went awry, operations such as the Holland invasion.

He and fellow soldiers from the “All American” 82nd and the 101st Airborne “Screaming Eagles” divisions were part of an unprecedented aerial attack of 35,000 allied paratroopers dropping from the sky into German-occupied Holland, 60 miles behind enemy lines. The airborne objective of the invasion, called Operation Market Garden, was seizing and controlling bridges across the Meuse and two arms of the Rhine rivers so allied armored divisions could quickly cross into Northern Germany unimpeded. While the 82nd was successful in securing key Netherlands bridges from Mook to Nijmegen, the ambitious operation did not go quite as planned for the British airborne, he says.

At Arnhem, the British 1st ran into strong resistance. A smaller force was only able to take and hold one end of the Arnhem road bridge — “a bridge too far,” declared a British general. Without adequate ground force support, the few who were still holding the bridge were soon overrun. The remainder of the division became trapped and had to be evacuated a few days later.

“The British 1st Airborne was a great outfit, but out of about 10,000 men, about 2,000 got through,” he says. “They had to swim back. They lost, and that’s what caused the Russians to get to Berlin before us.”

Do a quick Google search and read that of the 10,600 men of the 1st Airborne Division and other units who fought north of the Rhine, 1,485 died and 6,414 were taken prisoner of whom one third were wounded. Scan through the struggles of the 82nd that Trujillo did not mention, such as taking heavy fire from the Germans, at a cost of some 200 paratrooper’s lives, as members of his corps, along with the 504th and 505th — frantically fought — on shore and from boats, to secure the bridge at Nijmegen.

You realize as he talks about these epic struggles, which eventually combine to turn the tide against Hitler, he is in the middle of those horrors without the luxury of historical perspective and hindsight. It is one thing to read about it already knowing the outcome, but quite another to be there as it unfolds.

Battle of the Bulge

The Invasion of Normandy would have been more than enough. The struggles in Holland, certainly an apt bookend for Trujillo’s stories of war, but there is more. After being given a brief respite in France, he is sent to Belgium to fight in yet another epic World War II struggle, the Battle of the Bulge.

Once again, the 82nd and the 101st found themselves fighting together at different fronts. The 82nd was ahead of the 101st and made it to Bastogne and then kept going north to keep the Germans from further advancing around Elsenborn Ridge. They are called up in such haste, there is no time to swap out their summer uniforms. “It was a brutal winter,” he says.

In the course of this epic struggle, these two divisions prove crucial in the battle to prevent Hitler from splitting allied forces. They hold their ground and prevent the Germans from accessing key roads, despite being outnumbered and ill-prepared for the harsh weather conditions. He says that while his division was fighting to the north, the 101st made it as far as Bastogne before being cut off and surrounded by German troops.

This is the story of Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st, doggedly replying “Nuts!” to a German demand to surrender. Trujillo smiles as he recalls the terse response, “he was quite a guy.”

This is the noble account, but keep listening to Trujillo and soon you’re treated to a less-sanitized, human side of these war heroes as he candidly talks about the rivalry between the 101st and the 82nd and the ignoble fights that sometimes break out among them. Trouble always seems to follow when these two highly decorated divisions get together and alcohol is involved. One such time was in the days leading to the Bulge when they were together in a small village north of Paris for rest and relaxation. They will fight and die to defend Bastogne from the Germans, but watch out when they start fighting each other. The poor village they peacefully occupy, takes the less-than-peaceful brunt of their intoxicated interactions. “I remember seeing one who got so drunk that he walked through a glass door,” he says. “They destroyed that town.”

And they have hell to pay the following day from their commanding officer, Maj. Gen. James Gavin. Trujillo recalls Gavin telling them, “I am proud of you men whenever you are in battle; you are a great group of men. But you become animals; you disappoint me. Look at what you did to this city! You will be restricted.” Trujillo says that means “When the 101st gets to go out, we don’t, and when they stay, we go,” he laughs. “I don’t know, but I never could figure out some of these men in war. They were brutes!”

In his final battle, he tangled his arm in a parachute cord during a jump. “I’m lucky it didn’t pull it clear off,” he says. “What happened was a guy froze at the door. I had to push him out and while I was pushing him out, the cord got tangled around my shoulder. It spun me around real bad.” The injury, which landed him in the hospital, continues to plague him to this day.

He says that was the last time he was a paratrooper in the war. He is soon transferred from the 82nd and is placed in charge of an aerial photo distribution center. “I had a very tough assignment,” he says. “I had an office in Paris. All I had to do was wait for requests of photos from divisions and ship them out to them.”

Return from War

He remains in Paris through VE (Victory in Europe) day, May 8, 1945. By V-J day (Victory in Japan), Aug. 15, 1945, he is back home. The 82nd is called to fight in Japan, but he already has more than enough points to earn a discharge, and most certainly, he has had more than enough of war, he says.

He goes from jumping out of planes in ’45 to jumping back into the classrooms of BYU where he finishes his bachelor’s degree. He starts teaching at Carbon College in 1952. In between, he takes time off to complete a master’s degree in chemistry from Utah State University (where he recalls pleasant conversations with Merlin Olsen, future member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame and defensive tackle with the Los Angeles Rams. Olsen has a part-time job mopping the floors in his lab.) Trujillo goes on to earn a doctorate in fuels engineering from the University of Utah.

When he starts teaching again, Carbon College has morphed into the College of Eastern Utah. He is beginning to hit his stride, including letting go of some of the memories of his battles in Europe. By the time the ‘70s roll around, students know Dr. Trujillo as a demanding chemistry teacher, not the army intelligence officer he once was.

“I don’t recall any World War II stories,” says Scott Woodward, who took his class in 1975. He does recall, however, a few war stories of his own about the class.

“I tried to suppress those memories,” he jokes. “He was a very thorough teacher. He made sure that students who went through his class knew chemistry. As I am sure it is with most teachers and their subjects, chemistry, for him, was the most important thing in the world. He was very good at teaching. I still have nightmares of his exams. It was not a class you took for easy grades.”

Woodward apparently did just fine and turned out pretty well, too. Today he is world-renown for his work as a microbiologist and molecular biologist specializing in genetic genealogy and ancient DNA studies. He earned his doctorate at USU and went on to teach at BYU and the U of U. He currently teaches at Utah Valley University.

Boyd Nielson, pharmacist and owner of Boyd’s Family Pharmacy in Castle Dale, Utah, remembers taking chemistry from Trujillo in 1972, but he also doesn’t recall Trujillo ever talking about his World War II adventures. “I don’t think I was even aware of that part of his life story,” he says.

What he does remember is Trujillo’s sense of humor and gentle prodding whenever students asked him questions that he thought they should first try to figure out on their own.

“I frequently use a quote of his that I learned in his class,” Nielson says. “When someone asks a question, sometimes I’ll say, ‘you were born with that information.’ That was one of his favorite quotes that I remember to this day. Just delightful.”

Woodward says the Socratic method that Trujillo used to get his students to think for themselves and engage them in meaningful discussion is a technique he also has used over the course of his 30 years of teaching.

“He was very keen on asking probing questions that required more than just a one-word, yes-or-no, answer,” hesays. “You had to justify your answer. He required that you understand the subject matter and made you think about it.”

Being able to justify your answerstill reigns supreme for Trujillo. He fought a war that he knows was justified, to stop a madman who wanted toconquer the world. The justifications for wars that have since followed leave him questioning, including the Vietnam War where his son and namesake, Alfonso, fought and lost one of his legs as a U.S. Marine. The terrible wounds he suffered in that war are part to blame, Trujillo says, for his son’s early death.

“War is hell,” he says. And returning from such a place can take a long time. It haunts him still to think about how on three different occasions soldiers collapsed on top of him dead from enemy fire. “They died and I lived and I don’t know why,” he says. “Three times I hit the dirt, three times soldiers fell on me who were zapped.”

He considers war a last resort and says those who fight in it are never fully free from its clutch. “I feel very sorry for these young men who come back,” he says. “I can understand why so many of them commit crimes and get alcoholic.” He also understands why so many of them choose to simply shut down and withdraw, because he was once in that lonely place too.

“I hated how you lose individuality,” he says. “You become like anti-social or something. After the war, I got to where I hated people, I really did. Slowly that went away. I prayed hard for that.”

Boy oh boy, did he, as he did at Normandy and in Holland and Belgium, and as he now does for his own grandchildren facing their unknowns, for what else is there but prayer, he asks, when plunging headfirst into uncertainty? Like leaping out of a plane and hoping for the best.

~ John DeVilbiss